Understanding the Stock Market as a Game

There are differences, as we all know, between playing golf as a weekend player and a professional. These differences can be explained as the difference between a loser’s game and a winner’s game. That same difference can be used to understand why some traders win and others lose.

In his classic paper The Loser’s Game, Charles Ellis wrote,

“Simon Ramo identified the crucial difference between a Winner’s Game and a Loser’s Game in his excellent book on playing strategy, Extraordinary Tennis for the Ordinary Tennis Player. Over a period of many years, he observed that tennis was not one game but two.

One game of tennis is played by professionals and a very few gifted amateurs; the other is played by all the rest of us. Although players in both games use the same equipment, dress, rules and scoring, and conform to the same etiquette and customs, the basic natures of their two games are almost entirely different.

After extensive scientific and statistical analysis, Dr. Ramo summed it up this way: Professionals win points, amateurs lose points.

Professional tennis players stroke the ball with strong, well aimed shots, through long and often exciting rallies, until one player is able to drive the ball just beyond the reach of his opponent. Errors are seldom made by these splendid players.

Expert tennis is what I call a Winner’s Game because the ultimate outcome is determined by the actions of the winner.

Victory is due to winning more points than the opponent wins – not, as we shall see in a moment, simply to getting a higher score than the opponent, but getting that higher score by winning points.

Amateur tennis, Ramo found, is almost entirely different. Brilliant shots, long and exciting rallies and seemingly miraculous recoveries are few and far between.

On the other hand, the ball is fairly often hit into the net or out of bounds, and double faults at service are not uncommon. The amateur duffer seldom beats his opponent, but he beats himself all the time. The victor in this game of tennis gets a higher score than the opponent, but he gets that higher score because his opponent is losing even more points.

As a scientist and statistician, Dr. Ramo gathered data to test his hypothesis. And he did it in a very clever way. Instead of keeping conventional game scores – “Love,” “Fifteen All.” “ThirtyFifteen.” etc. – Ramo simply counted points won versus points lost.

And here is what he found. In expert tennis, about 80 per cent of the points are won; in amateur tennis, about 80 per cent of the points are lost.

In other words, professional tennis is a Winner’s Game – the final outcome is determined by the activities of the winner – and amateur tennis is a Loser’s Game – the final outcome is determined by the activities of the loser.”

Ellis concluded, and a recent article in Institutional Investor confirmed that “Investing in public markets has become a loser’s game, and probably has been for a long time.”

This shift is seen in asset flows to passive managers.

Source: Institutional Investor

Beating the Market

In simplest terms, the experts are telling the average investor to follow the well known advice “if you can’t beat them, join them.” This means passive index funds are increasingly popular and that sets up an interesting dilemma that individual investors must consider:

If the stock market declines by 50%, is it really your goal to lose 50%?

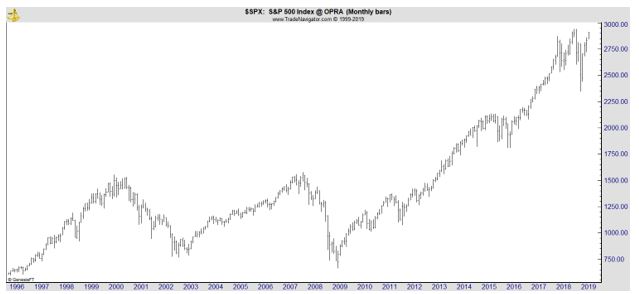

Remember that the stock market has declined by 50% twice in the still young 21st century.

Investors often seem to forget about those brutal losses in bull markets. The experts begin explaining that it is impossible to beat the market in the long run and highlight bull market returns. When bear markets are considered, active strategies can be useful.

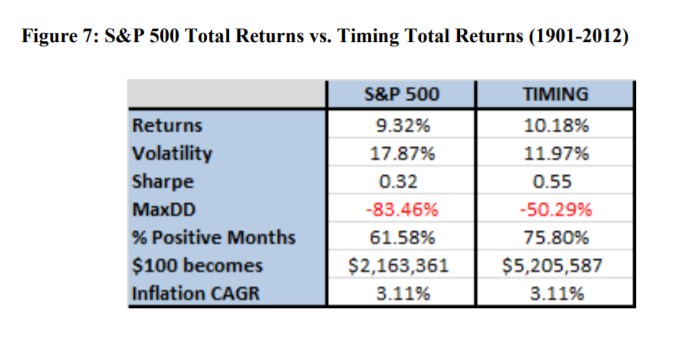

In A Quantitative Approach to Tactical Asset Allocation, Meb Faber noted,

“In his 2008 book Stocks for the Long Run 5/E: The Definitive Guide to Financial Market Returns & Long-Term Investment Strategies, Jeremy Siegel investigates the use of the 200-day SMA in timing the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) from 1886 to 2006.

His test bought the DJIA when it closed at least 1 percent above the 200-day moving average, and sold the DJIA and invested in Treasury bills when it closed at least 1 percent below the 200-day moving average.

He concludes that market timing improves the absolute and risk-adjusted returns over buying and holding the DJIA. Likewise, when all transaction costs are included (taxes, bid-ask spreads, commissions), the risk-adjusted returns are still higher when employing market timing, though timing falls short on an absolute return measure.”

Faber then tested an even simpler strategy using the 10 month moving average. His results are shown below.

Source: A Quantitative Approach to Tactical Asset Allocation

Source: A Quantitative Approach to Tactical Asset Allocation

Notice that the simple timing model beat the long term passive investment model. That’s because of the important impacts bear markets have on long term performance.

Faber explains, “All of the G-7 countries [G-7 countries are the world’s largest developed economies] have experienced at least one period where stocks lost 75% of their value.

The unfortunate mathematics of a 75% decline require an investor to realize a 300% gain just to get back to even – the equivalent of compounding at 10% for 15 years!”

A 50% loss requires a 100% gain just to get back to even. That could take many years or even decades. To this, the passive investment advocates note that stock prices always come back and that advice requires ignoring Japan which is not really an anomaly.

Japanese stocks peaked in 1989 and remain well below that all time high. In fact, after thirty years, the benchmark average for that country remains more than 40% below its all time high. Ignoring that reality places an individual’s retirement at risk. That is irresponsible and yet, many investment experts insist that risk should be ignored.

Given the high level of risk and life changing consequences, buy and hold passive investing might be too risky for almost all individual investors.