Is Value Investing an Art or a Science?

Doctors often describe medicine as part science and part art. What they mean by that is diagnosing a set of symptoms seems like something that is based in science. But, there is an art to the diagnosis. That’s because some cases are simply unique and sometimes, symptoms overlap.

When symptoms overlap, a fever for example, the symptom could point to multiple factors. Running through a checklist to identify additional symptoms could narrow the possibilities of diagnosis but that could be timely and there will be times when time is short.

Since there can be so many possibilities for some patients, experience can be useful. This is where the art comes in. The diagnosis will still be grounded in science, but the practitioner will have developed knowledge which helps them act faster and more accurately at times.

The same will apply to treatment options which require a combination of science, experience and art. This is true not just for medicine but also to a number of other professions.

Value Investing as Science

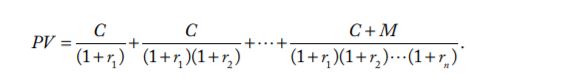

Value investors often believe they are dealing with a precise process. For example, they might use a simple formula for finding the fair value of a stock such as the discounted cash flow (DCF) model.

Source: CFA Institute

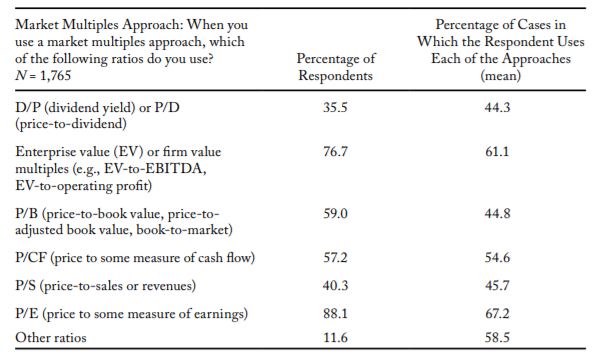

As an alternative to the DCF model, analysts may choose to use a number of other models. A market multiple model may be more popular among individual investors than the DCF model which may be used by professionals.

As an aside, a recent survey found that more professional investment analysts use a market multiple approach than a DCF model. In the survey of 1,980 market pros, 68.6% reported using the multiples model at some point while 59.5% used a DCF approach. Professionals often use multiple approaches in their work.

Market multiples are tools to determine the price of an asset relative to the price of comparable asset. So, they establish a ranking of asset values. For example, they tell us which one of a group of stocks is the most overvalued and which is the most undervalued.

There are a variety of multiples available. For example, there is the price to earnings (P/E) ratio. The P/E ratio compares the stock’s current price (P) to its earnings per share (E). Earnings could be the historical earnings, projected earnings, average earnings over some number of years or adjusted earnings.

Other popular multiples include the dividend yield, the price to book (P/B) ratio, price to sales (P/S) ratio, the price to cash flow (P/CF) ratio and various ratios based on enterprise value (EV).

The P/E ratio may be the most popular multiple among individual investors and it is also the most popular among market pros.

Source: CFA Institute

There are other approaches that are used by professionals and individuals. All of these approaches rely on data and formula, but none will ever be 100% reliable. That explains, in part, why there are so many different approaches and why there is no guarantee of success.

Value Investing as Art

One of the greatest value investors of all time is Warren Buffett, an individual who has created billions of dollars of wealth with the principles of value investing. He describes his approach in relatively simple terms.

Buffett reads annual reports and develops a value of what he believes the owner’s earnings should be. This can be roughly approximated as earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization with required capital expenditures added back in.

After finding adjusted earnings, Buffett then discounts those earnings to find the net present value of the projected earnings. He has written that he uses the interest rate on the ten year Treasury note as his discount rate.

Now, even after Buffett explains all that, we know that no one else seems to be able to do that. While Buffett describes his process in terms that sound scientific, there is clearly and art to what he does. If there was not, then others would be able to duplicate his process.

Can Value Investors Beat the Market

Acknowledging there is not an art and a science to valuation methods, the question is whether or not investors can beat the market. The answer is “it depends.”

There are certainly many individuals trying to beat the market.

The number of investors is growing. Graham and Dodd wrote their seminal book Security Analysis: Principles and Techniques in 1934. Some 20 years later, roughly 4% of the US population owned stocks.

Another 40 years later, that figure had grown fivefold: 20% of the US population owned stocks (including stock mutual funds), thanks largely to the introduction of individual retirement accounts (1974) and the first index funds (1976).

There is certainly ample opportunity to beat the market.

The investable universe was still largely domestic and small: 2,670 listed firms in the United States in 1975, according to the World Bank. According to the same database, only 1,398 firms were listed in Japan in 1975, 471 in Germany, and none in either China or India.

By 2016, the number of listed firms worldwide had exploded to 43,192, of which only 4,331, or 10%, were in the United States; China (3,052) and India (5,820) together accounted for 20% of all listed firms worldwide. The number of listed firms for Germany in 2016 was 555 and for Japan 3,504.

Investors looking for returns have many more options than they ever did in the past. But, the role of the investor needs to adapt in this environment.

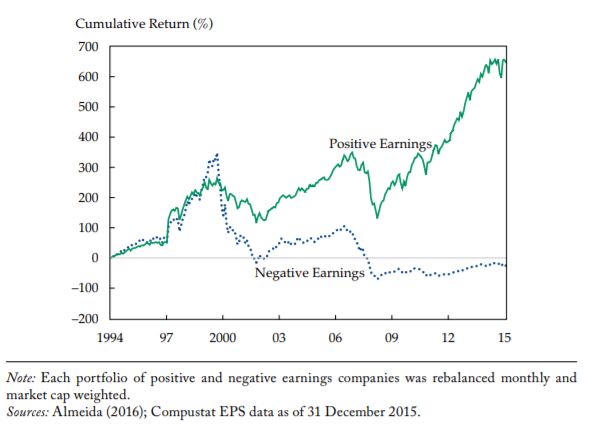

To beat the market, it is important to focus on what matters the most. Despite all of the distracting information available, earnings matter.

Source: CFA Institute

In the long run, earnings matter. This has become especially important as access to information has expanded. Companies with negative earnings have underperformed in this century. Simply looking for earnings, now or in the near term, could boost investment returns.

Now, the art comes in deciding which earnings to use. Like Buffett, it could be useful to adjust earnings, a skill that will take time to learn and apply.

For other market related tips, Click Here.