Here’s What Really Happens In An IPO

We often see reports of initial public offering (IPO) tinged with excitement. There is anticipation prior to the first day of trading and then there is often a big price move the day of the trade. CNBC might show a celebration at the company’s offices and the ticker shows a large gain.

But who really makes money on these IPOs?

The Process Is Transparent

An IPO is defined as “the process of offering shares in a private corporation to the public for the first time is called an initial public offering (IPO).

Growing companies that need capital will frequently use IPOs to raise money, while more established firms may use an IPO to allow the owners to exit some or all their ownership by selling shares to the public.

In an initial public offering, the issuer, or company raising capital, brings in underwriting firms or investment banks to help determine the best type of security to issue, offering price, amount of shares and time frame for the market offering.”

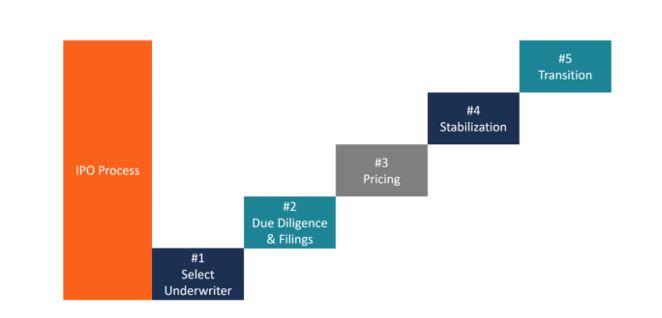

The process itself is time consuming, taking months to complete and the steps can be summarized in the chart shown below.

Source: CorporateFinanceInstitute.com

There are several important points for individual investors to remember.

Pricing is determined by the company in consultation with the investment bankers managing the deal. The investment bankers propose an initial price to the company and then the company completes presentations to large investors in what is commonly called a “road show.”

The road show allows investors to comment on what they believe the price of the stock should be. Using all of that input, the price is finalized the day before the stock begins trading. Shares are then sold at that price to a select group of customers.

This a process known as allocation and experts note, “public offerings are sold to both institutional investors and retail clients of the underwriters.

A licensed securities salesperson (Registered Representative in the USA and Canada) selling shares of a public offering to his clients is paid a portion of the selling concession (the fee paid by the issuer to the underwriter) rather than by his client.

In some situations, when the IPO is not a “hot” issue (undersubscribed), and where the salesperson is the client’s advisor, it is possible that the financial incentives of the advisor and client may not be aligned.

The issuer usually allows the underwriters an option to increase the size of the offering by up to 15% under a specific circumstance known as the green shoe or overallotment option. This option is always exercised when the offering is considered a “hot” issue, by virtue of being oversubscribed.”

The shares that are traded on the first day of trading are the shares that were allocated to large customers the day before. That means by the time an average individual investor can buy shares, the process has already moved beyond the IPO phase. Initial trading is often exuberant and costly to individuals.

Uber As an Example

Uber, according to CNBC, “seeks to raise about $9 billion in cash in its initial public offering next month when it is expected to debut on the New York Stock Exchange under the symbol “UBER.”

The company plans to offer 180 million shares at $44 to $50 per share, according to an updated filing released Friday morning, valuing the company between $80.53 billion and $91.51 billion on a fully diluted basis.

The valuation is well below earlier reports that suggested Uber could be valued as high as $120 billion. At the low end of its price range, Uber’s market cap would be $73.7 billion, which would even fall below its last private valuation of about $76 billion.

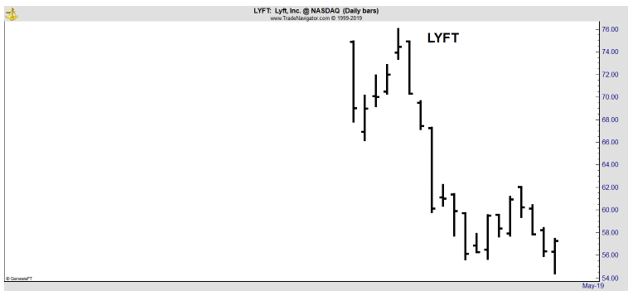

Even at the lower end of its pricing, Uber will still be the largest tech IPO to debut this year. The company may have scaled back expectations after seeing excitement around its rival Lyft’s stock quickly fizzle out.

The stock, which has a market cap of about $16 billion, is down more than 27% for the quarter since debuting in late March.

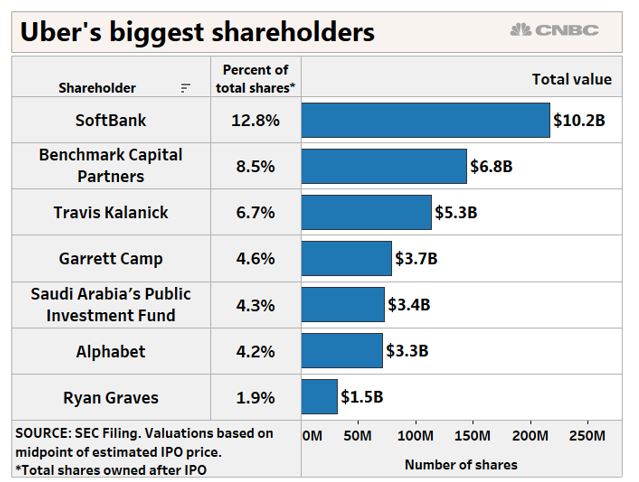

Still, Uber’s IPO is set to make its top shareholders worth billions. Assuming Uber prices at $47 per share, the midpoint of its stated range, SoftBank stands to gain the most from the IPO. Based on its post-IPO share count in the filing, the firm would earn more than $10 billion in the offering.

Even Uber’s ousted former CEO and co-founder Travis Kalanick stands to gain $5.3 billion in the IPO, based on the same assumptions. His co-founder, Garrett Camp, stands to gain about $3.7 billion through LLCs he manages, under these assumptions.

Here’s where each major shareholder will stand after the public offering, based on their post-IPO share counts and assuming Uber prices at the midpoint of its stated range at $47 per share:

Source: CNBC

Not all of these investors are selling. According to Bloomberg, “Benchmark is the biggest seller, offering 5.7 million of its shares, according to a regulatory filing [recently file]. That would fetch about $270 million at the middle of the listing’s current $44 to $50 price range.

SoftBank Group Corp. is offering 5.5 million shares, while Uber co-founders Travis Kalanick and Garrett Camp expect to sell holdings worth $176 million and $147 million, respectively.

Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund and Alphabet Inc. haven’t offered any of their shares for sale.”

If Uber rises at the open, the initial sellers, including Benchmark, SoftBank and Kalanick, will benefit from the holdings they retained. The shares they sold, to large hedge funds, will be sold by the investors who received shares in the allocation process.

Initial trading will benefit investors who owned the shares less than a day. Individuals will buy shares at the open and may see losses mount as they did with Lyft.

In any event, the insiders can sell all of their shares after a lock up period, typically 30 to 90 days after the IPO and this could drive the price down as it has for other tech stocks.

In short, in an IPO, smart money is selling to less informed investors and the individuals chasing the excitement are among the most likely to suffer losses.