Finding Safe 5% Yields

Yields are elusive, especially high yields in the current market environment. Published yields can also be deceptive and may not really be available to investors. That’s because of an all too often overlooked investment cost, taxes.

For at least some investors, taxes are considered near the end of the year. The end of year tax planning is often applied solely to the stock market and involves reviewing trades, trying to find losses that can be recognized in order to offset gains that are taxable.

Gains, in taxable accounts, are reduced by an investor’s tax rate. Capital gains can enjoy a favorable tax rate. But, that same favorable treatment does not apply to fixed income investments.

That means, on an after tax basis, income investments might offer lower than expected cash flow to investors who forget taxes.

Tax Planning Should Not Be Just For High Net Worth Investors

High net worth investors, those with significant investable assets that are $1 million or more, have access to sophisticated planning strategies. Their plans can include tax savings tools like using municipal bonds that pay relatively low yields.

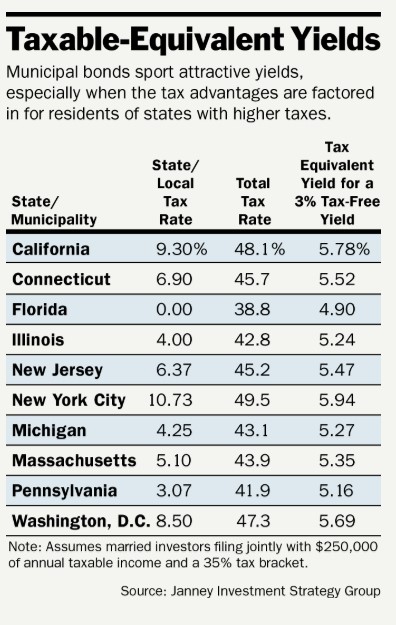

However, the low yields need to be adjusted for the tax savings in order to make a true comparison with taxable bonds. It’s important to look at the taxable-equivalent yield, which factors in the tax benefits that municipal bonds, or munis, provide.

The biggest benefit is that the interest paid by munis is typically exempt from federal taxes. For an investor residing in the state in which a municipal bond was issued, state and local income taxes are usually exempt, as well. In high tax states, this is an important benefit to high net worth investors.

But, “It’s not just a marginal benefit for a high-income investor to invest in munis. It’s a very large benefit,” says Alan Schankel, a managing director and municipal strategist at Janney Investment Strategy Group, recently told Barron’s.

The table below shows the tax equivalent yields under various scenarios.

Source: Barron’s

Finding the Real Yield

The calculation of a taxable-equivalent yield is fairly straightforward. You begin by finding the stated yield and divide it by one minus the tax rate.

As an example, consider a married California couple whose income is $250,000: A municipal bond’s stated yield is 3% and their total tax rate is 48.1%—35% for the feds, 3.8% for Medicare, and 9.3% for state taxes. One minus 0.481 is 0.519.

Then divide the interest rate by that value, so 3 divided by 0.519 gives you a taxable-equivalent yield of nearly 5.8%. That’s nearly twice as high as the stated yield, according to the examples cited by Janney.

That is apparently a significant benefit for a high income family. But, what if you aren’t earning $250,000? Well, if you are self employed in a high tax state, then you might still be heavily taxed.

According to the IRS, “you usually must pay self-employment tax if you had net earnings from self-employment of $400 or more. Generally, the amount subject to self-employment tax is 92.35% of your net earnings from self-employment.”

This rate consists of 12.4% for social security and 2.9% for Medicare taxes, a combined 15.3%. But, TurboTax explains, you can claim 50% of what you pay in self-employment tax as an income tax deduction.

For example, a $1,000 self-employment tax payment reduces taxable income by $500. In the 25 % tax bracket, that saves you $125 in income taxes. This deduction is an adjustment to income claimed on Form 1040 and is available whether or not you itemize deductions.

You can see the deduction reduces the tax, but it is still significant. This in addition to federal income taxes and state or city income taxes and even a self employed individual with a relatively average income could face a significant tax rate.

Another thing to consider is that under the revised tax code, the deduction for state and local taxes, or SALT, is capped at $10,000. That’s especially important in certain states with higher local taxes such as New York, New Jersey, and California, as the accompanying table shows.

“I would argue that munis are more attractive than they’ve ever been because, with the loss of various deductions, including SALT, one’s taxable income is higher than it’s ever been,” Robert Willens, who runs tax consultancy Robert Willens LLC, explained in Barron’s.

Now, Where to Find Safe 5% Yields

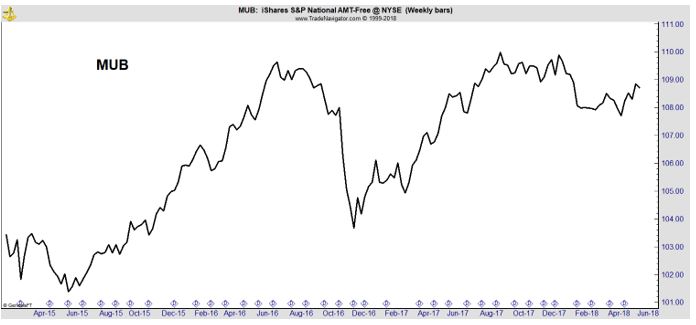

It is important to remember that like any other fixed income investment, municipals will lose value as interest rates have risen. The iShares National Muni Bond exchange-traded fund (NYSE: MUB), which tracks the S&P National AMT-Free Municipal Bond Index, has lost 0.55% this year.

This fund consists of investment grade credits.

The recent yield on MUB is 2.3% although the real tax equivalent yield is determined by your individual tax situation.

Catherine Stienstra, head of municipal-bond investments at Columbia Threadneedle Investments, told Barron’s that the Bloomberg Barclays Municipal Bond Index has returned a little more than 1% this month, partly owing to supply constraints. “This year, we are expecting even more supply constraints,” she adds.

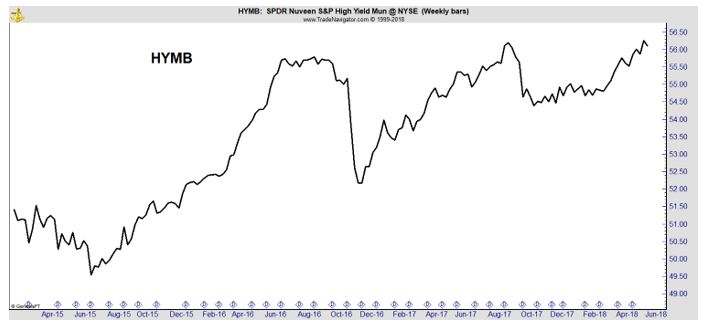

High yield munis have fared better. Compared with investment grade credits, high yield bonds are much more of a play on credit risk. However, with the U.S. economy in pretty good shape and tax receipts healthy, high yield munis for the most part haven’t caused a lot of worry among investors.

The SPDR Nuveen S&P High Yield Municipal Bond ETF (NYSE: HYMB) has returned about 2.88% year to date, a respectable result. But remember that these bonds are classified as high yield for a reason, notably additional credit risk, so some caution is needed.

This fund recently yielded about 3.4% and, again, the real tax equivalent yield is determined by your individual tax situation.

These bonds have long been used by high net worth investors and there is a reason for that. There are significant tax savings for high income individuals.

However, even people with less income than top earners can benefit from tax savings. Munis are worth considering, especially if you are self employed and subject to state income taxes.