Five Stocks Under $5 That Warren Buffett Might Buy, If He Could

Warren Buffett is a great investor, but he really can not do everything that we, as individual investors, can do. Some investors may not realize that we have an advantage over Buffett in some ways.

Let’s say Buffett found a great insurance company with a market cap of $400 million. We know that Buffett loves insurance companies.

One news story recently highlights Buffett’s love of the industry, “Feb. 22, 2019, it will be 52 years to the day since Warren Buffett took his first serious dive into the insurance business when Berkshire Hathaway entered into an agreement to acquire National Indemnity Company and another smaller insurer for $8.6 million.

National Indemnity is still a part of Berkshire Hathaway 52 years later, and one that Warren Buffett values highly. In fact, Warren Buffett told shareholders in 2004 that if Berkshire hadn’t acquired National Indemnity, “Berkshire would be lucky to be worth half of what it is today.”

To put it mildly, Buffett loves the insurance business. Since acquiring National Indemnity, Buffett and his team have made many other insurance additions, including GEICO in 1996, General Re in 1998, and more.”

Insurers invest the money they collect as premiums that have not yet been paid out for claims. This cash flow is referred to as the float in the industry.

Experts note, “Most insurance companies invest the majority of their float in low-risk investments. For an example, think Treasury securities and some corporate bonds. Buffett, on the other hand, takes a somewhat different view and has used the float held by Berkshire’s insurers to invest in equities and acquisitions of other companies.”

Yet, it seems fairly certain that if Buffett found an excellent $400 million insurer, he would not buy it.

That’s less than 0.01% of the value of his investment portfolio. If the insurer does great and doubles in value Buffett would increase the value of Berkshire Hathaway by less than 0.01%.

More realistically, let’s say he gets a 20% return on his investment. That increases his portfolio value by $80 million or less than 0.002%.

Buffett made $500 million a year in dividends on an investment in Goldman Sachs that he made in the depth of the 2008 bear market. This is the kind of return he needs to continue growing Berkshire and given that requirement, he simply can’t look at small caps.

This is where we, as individual investors, have an advantage over Buffett. We can buy small cap stocks because 20% gains mean a great deal to us. One way to exploit this advantage is to study Buffett’s deals and apply his valuation principles to small caps.

Finding Break Out Patterns

We could quantify the kind of stock we believe Buffett likes. In the letter to shareholders he writes every year, Buffett has mentioned that he measures management with an accounting tool called return on equity (ROE).

The is the ratio of net income to shareholders’ equity. ROE measures the percent of profit management is earning with the money shareholders invested in the company. ROE can vary by industry so a detailed analysis is usually needed to understand how well management is performing relative to its peers.

For our purposes, we are looking for the best small caps so we will require companies to have an ROE of at least 15%. This level is better than the ROE reported by about 70% of all publicly traded companies. This limits our search to the best management teams in the country.

We could also require the company to have a higher than average return on assets and a history of increasing sales. By requiring that sales be increasing over the past five years, we are eliminating stocks which have no operating cash flow and that could be headed towards bankruptcy.

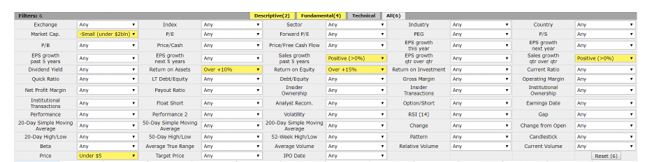

One way to find stocks meeting these requirements is with the free stock screening tool available at FinViz.com. At this site, you could screen for a variety of fundamental factors, high levels of institutional ownership and bullish institutional transactions Or, you could just screen on new highs. An example is shown below.

Source: FinViz.com

For this screen, we selected stocks that Warren Buffett might like and that are too small for him to realistically take a significant stake in.

This screen is a reasonable starting point for additional research. There is no guarantee any of these stocks will deliver gains and risk should always be considered. It’s also important to remember that screens like this will not identify unique risk factors.

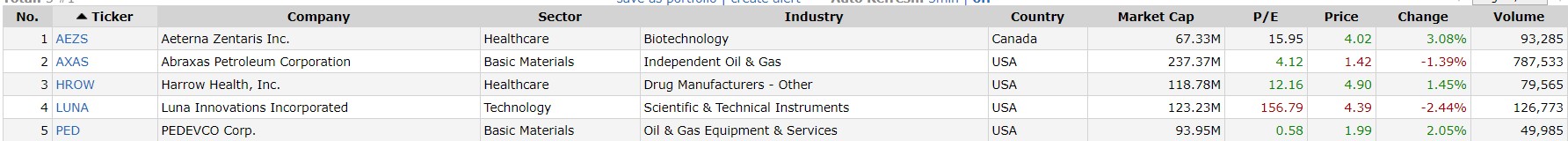

Stocks passing the screen are shown below.

Source: FinViz.com

Aeterna Zentaris Inc. (Nasdaq: AEZS) is thinly traded but prone to make large moves.

A stock like this could be bought and sold by aggressive traders looking for small gains. For example, a buy could be made and immediately after that order is filled, a profit taking sell order could be entered. If the stock spike higher, as it has in the past, a strategy like that could deliver gains.

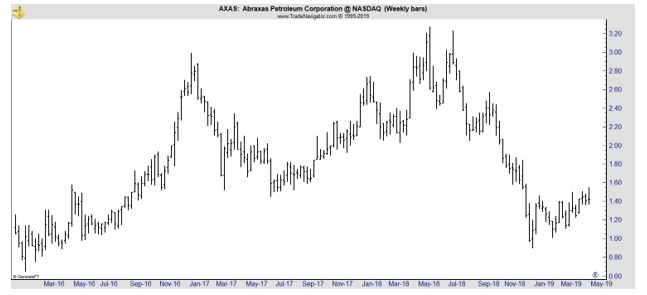

Abraxas Petroleum Corporation (Nasdaq: AXAS) is in a down trend.

But the stock is in the energy industry and many experts believe there is bullish potential in this sector.

Harrow Health, Inc. (Nasdaq: HROW) is also in a down trend and could be attractive to value investors looking for a turn around.

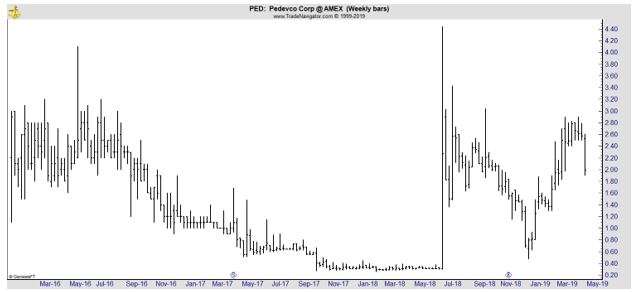

PEDEVCO Corp. (NYSE: PED) is in a trading range and could be prone to make large moves on news. This could be a stock of interest to the most aggressive investors.

Luna Innovations Incorporated (Nasdaq: LUNA) is in an up trend and could be a stock that interests momentum investors.

These stocks could all deliver significant gains or could all prove to be worthless. That is the risk of any investment but the potential gains in small cap stocks can be large while the potential risks are limited to the price paid at the time of purchase.

Each of these stocks, in particular, could be worth additional research since they display at least one quality Warren Buffett could look for.